Longwood, Florida

U.S. Army, 9th Infantry Division, Bronze Star and Purple Heart

I grew up in a small town outside Pittsburgh and graduated in 1966 in the last class of Washington Township High School before it merged with another nearby school. During the next few years I attended Edinboro College (now University) near Erie, Pennsylvania but decided to take a break prior to receiving my diploma. I got married, had a son, Dennis Jr., and at age 20 got drafted. I had already used my student deferment – you only got one – but even though I was married with a son, I was considered 1-A. My attitude was, “Whatever will be, will be.”

I reported for duty December 10, 1968 and was sent to Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina for basic training (eight weeks) and infantry training (nine weeks). Following a four-week leave to visit my family, I was shipped off to Vietnam on May 24.

While on patrol in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, I became a triple amputee as a result of a land mine explosion. While I don’t remember the explosion itself or flying through the air, I do remember falling back down to the ground and realizing the extent of my injuries. That’s when I started to lose it, but my sergeant calmed me down by slapping me and reminding me of my family waiting for me back home. My fellow soldiers kept me alive and conscious so I wouldn’t go into shock before the medevac helicopter arrived.

The medic got there and my sergeant, who we called Gomer, helped him stuff these heavy cotton gauze packets in my wounds. They put a tourniquet around my arm, just like you see on TV, with the stick to tie it and all that. Somehow they were able to stop the bleeding.

I don’t think the medic ever saw anybody so messed up and still living. Doc was trying to give a shot of morphine. I looked over at him, and that needle in his hand looked to me like a runaway sewing machine. I actually had to hold on to his arm to steady him so he could give me a shot.

I’ve often thought about him and how glad I am it wasn’t me coming up on someone else who looked like I did because I’m not sure I would have had what it takes.

My recovery began the next month at Valley Forge Army Hospital under a young surgeon, Dr. Craig Roberts, who was not yet 30 years old. My wounds eventually healed cleanly, and although I was fitted for prosthetics, I opted for a wheelchair. It was a pretty short time frame – five months – for losing three limbs. I think it was pretty quick healing.

The kind attention given me by Dr. Roberts pulled me through. Nobody was any more loved than Doc Roberts. It wasn’t so much the medicine, the doctoring. The thing with Doc – he just believed in us.

We had two 30-minute physical therapy sessions a day, and the rest of the time the other amputees and I played sports and got a bit rambunctious. Finally, a sergeant gave us a stern talking about our behavior but Doc Roberts pulled him aside and convinced him our game-playing was good for our healing.

I did well through the rehabilitation process. I never really had any problems dealing with it. I made up my mind real quick that the world is turning and it doesn’t care if Dennis is on it or not. Somehow, some way, you keep going.

I built a house and then went back to college for a degree in accounting. I got a job at the Westmoreland County Juvenile Service Center in Pennsylvania and worked my way up to become administrator for the entire county court system.

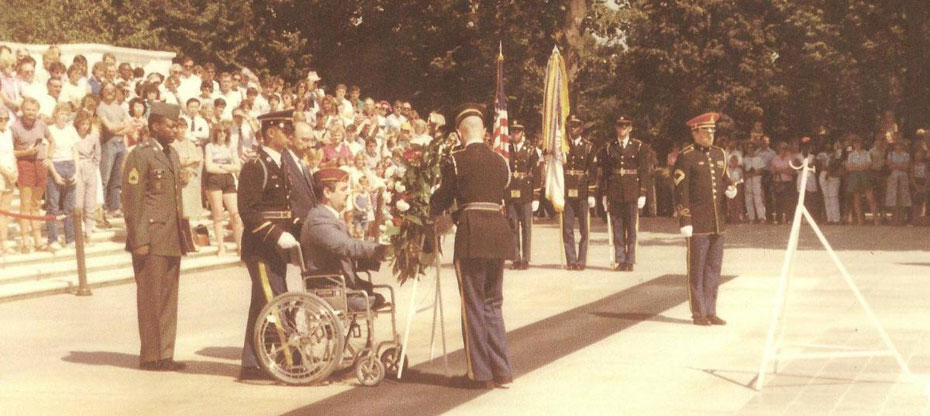

I got involved in the DAV through my mailman, who invited me to my first meeting, and eventually I served in every elected office in my chapter, including commander. I was named Disabled Veteran of the Year in Pennsylvania and then the DAV’s National Outstanding Disabled Veteran of the Year. After that, things kind of took off. A couple of years later I became a national officer and then national commander, so I traveled all over the United States and did a lot of speaking. President Reagan named me Handicapped American of the Year.

Then I retired at age 40 and moved to Florida. That lasted about six weeks. I took a “retirement” job for the next nine years as a budget analyst for Seminole County until I was appointed Assistant Supervisor of Elections and then Supervisor of Elections. I did finally retire in 2005.

I’ve always kept my focus on what disabled people can do, on solutions rather than problems. Awareness is crucial. And for me, personally, keeping active athletically helped me in my rehabilitation and involvement in so many outside activities. I coached my son’s baseball team. I belong to a health club, swim and bike, and have skied and water-skied. I’ve always been a hunter.

Other hunters see me out in the wood, I’m sure they want to run. The first deer I ever got, I don’t think I hit it. I think it died of a heart attack. It came running into the middle of this field and saw me sitting in a wheelchair with a gun and said, “You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Wife Donna Joyner:

“Her Daddy Doesn’t Have Any Legs!” As I sit here 23 years later, I can still hear those words being said by one of my daughter’s kindergarten classmates and the laughter that filled the room. All the children laughed except for one, my daughter Kristen. As tears filled her eyes, she said, “Why are they laughing at my daddy?

Thankfully, Kristen’s teacher, Mrs. Isaacson heard the children’s comments and was well aware of the injuries Kristen’s daddy had sustained during the Vietnam War. Mrs. Isaacson asked if my husband Dennis would come to the classroom and talk with the children about his experience in Vietnam and how he became a triple amputee.

Dennis readily agreed and off we went to visit Kristen’s classmates. Upon arriving at the classroom, things got pretty crazy, with one little girl starting to cry and screaming “Get him away from me!” As you can imagine, it must have been really traumatic to see someone missing three limbs and being in a wheelchair, especially to a five-year-old. But to Kristen it was normal, that was her daddy.

After order was restored, Mrs. Isaacson asked the children to sit on the floor and form a semi-circle around Dennis’ wheelchair. All of the children sat down but sat as far away from Dennis as they possibly could. As Dennis started to explain what happened to him in Vietnam, why he was in the wheelchair and had a prosthetic arm, the children’s questions started to fly. How do you eat? How do you get in bed? How do you get dressed and how do you drive a car? Can I touch your fake arm and how do you get the hand to open and close?

After all the questions were answered, the best thing that happened was that the children were no longer sitting as far away as possible but standing around Dennis, touching his prosthetic arm and his wheelchair and knowing that he was no different than their daddy, he just did things a little differently.

What the Memorial Means to Me

Finally, a Memorial that will recognize and remember the lives of pain and suffering that I and my fellow disabled veterans have had to endure. A Memorial that stands to honor the sacrifices forced upon my parents, my wife and my children. A Memorial that will remove those haunting words I relive every day that I screamed on the jungle floor of the Mekong Delta in South Vietnam, “Let Me Die,” as I visualized the loss of both my legs and my arm. Finally, a sense of satisfaction knowing what I gave, and my family and I continue to give, will be forever remembered.

REMEMBER….the sound of my cries and visualize the loss of both of my legs and my arm as I lay wounded on the jungle floor in South Vietnam.

REMEMBER….the sound of my mother and father’s hesitant footsteps on the wooden floor of the Army Hospital the first time they came to visit me.

REMEMBER….the pain and suffering that I and so many other disabled veterans endure for our FREEDOM.

REMEMBER….as you stand view the American Veterans Disabled For Life Memorial, we did it for you.

Finally, a Memorial that provides me a place to reflect back on my life as a disabled veteran.

Hearing my mother so often talk about the fear she had within as she walked through the hall of Valley Forge Army Hospital on her way to see me for that first time after losing my legs and arm. Being told how my father angrily responded that I would be fine after a friend told him it was a shame what happened to me. And after being excited to receive artificial legs at age 21, only to later realize I would be more mobile living my life in a wheelchair. And what did my adult son mean when he told my wife to keep an eye on our daughter because being my father’s child is not easy?

Yes, this is my Memorial for me to reflect and remember my life as one who gave three limbs defending the freedoms we so dearly cherish and for all those who live it with me.

It is a Memorial that will provide those whose lives haven’t been affected by the ongoing consequences war causes to understand that war, for some, lasts a lifetime.